Honestly, I thought it was some sort of April Fool's issue of Sport's Illustrated leftover on the stands. But much to my chagrin—and the annoyance of the guy looking at Newsweek who I almost body slammed to reach for a copy—I found it to be a real and fun way to get my science news.

I picked up the May/June 2008 issue and could tell right away that some of the articles were a tad dated. But one busy lady can't read it all, so I did find several fascinating tidbits that were totally new to me.

For example, seems some European scientists have been trying to figure out how the brain manages to use electrical impulses to communicate signals without giving off heat. Their answer: It doesn't.

As any first-year physicist can tell you, the laws of thermodynamics state that you can't create or destroy energy. Mechanical processes such as, say, charged salts passing through ion channels—the long-held method by which electrical impulses travel along nerves—must generate heat.

Trouble is, experiments on brains in motion can't find any such heat.

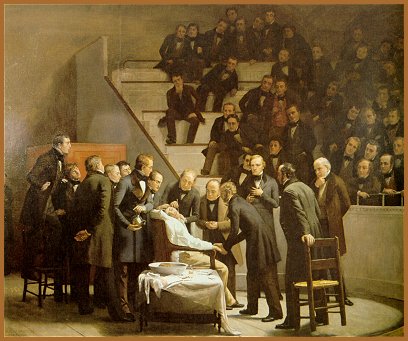

Then there's the fact that experts have been hotly debating for centuries exactly how anesthesia works and why inflammation makes it less effective.

Instead, researchers at the university's Niels Bohr Institute and Germany's Max Planck Institute think that brain impulses are actually special sound waves called solitons. Unlike normal sound waves that lose their oomph over distances, solitons are like the Energizer Bunny: They keep going and going, provided the medium they're traveling in is at just the right temperature to hover between liquid and solid.

As it happens, that's just the right temperature of lipid membranes in nerves. And that would offer a handy explanation for why anesthesia craps out on you if your nerves are inflamed. According to the researchers, pain blockers change the melting point of lipid membranes, causing them to become mostly solid and thus blocking solitons. But inflammation masks the effect, making anesthetics less potent.

That's not to say there's no juice flowing when the brain is firing; plenty of experiments have shown proof of the electric sparks inside our heads. But the researchers put those signals down as ancillary to the sound waves—a byproduct, not the root cause.

Based on what I read in Science Illustrated, the soliton scientists make a pretty interesting case. I'll be looking forward to seeing if they set up some experiments to test what could be a very, uh, sound theory.

2 comments:

That is really cool! Thanks for posting!!

I was into it...all the way up to the pun.

Post a Comment